In an op-ed in the Montreal Gazette this past week, I argued that effective bullying prevention requires, among other things, the teaching of tolerance and acceptance of diversity.

In an op-ed in the Montreal Gazette this past week, I argued that effective bullying prevention requires, among other things, the teaching of tolerance and acceptance of diversity.

It sounds like one of those obvious statements that should just be a given. Of course we need to be accepting of those who are not like us! Who would argue with teaching our kids about civility and respect?

Well, lots of people actually. Like those in the current Quebec government trying to enact a law preventing public workers from wearing a turban, hijab or yarmulke or any other religious symbol (except possible a cross). Or those who believe homosexuality equals sin. Or those who believe the colour of one’s skin and choice of clothing makes them inherently more dangerous.

But I digress. Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that we can all agree we want to teach our children to be respectful of differences (and hope this will some day be true). We’d like to think that parents will do this at home, of course, but whether they do or not, we’d like to see it reflected in their schooling.

So what does teaching tolerance actually look like? What does it mean on the ground for the teacher with 32 grade schoolers sitting in rows in front of her (or his) desk? What can she say? What does he do?

One of the best lessons I’ve read about what teaching tolerance actually looks like comes from a magazine with that exact name. The Southern Poverty Law Center‘s fabulous biannual magazine, Teaching Tolerance, featured an award-winning feature by Paul Roud called “Meeting Matthew.”

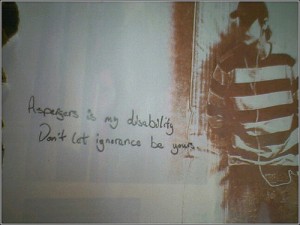

The situation? A new 7th grader coping with Asperger’s Syndrome. The otherwise bright and friendly boy picked his nose constantly, yelled out remarks in class and said things to other students that came across as mean and aggressive. The other students perceived him as “strange,” because he’d walk down the hallways with books piled on his head.

Let’s be honest: students like this can test the patience of teachers as well. These kids aren’t always so sympathetic, and the classroom disruptions and socially inappropriate comments can start to feel personal. Teachers are human too. As the writer points out, any student who stirs negative emotional reactions in their teachers is likely to do the same in the other students. In this case, the principal noticed that the boy was starting to be socially isolated by his peers.

Because Asperger’s is a hidden disability, it can be harder to engage the understanding and tolerance of others. Individuals appear perfectly normal and typically have average or above average intelligence. However, their communication skills are not typical. They can have great difficulty making sense of the social cues most of us take for granted, such as facial expressions, common social protocols and body language. It can be harder for them to understand or show empathy to others. Kids with Asperger’s are therefore at very high risk for bullying by their peers.

The solution? A “disclosure meeting.” With the support of Matthew and his parents, the principal decided to explain his situation in a meeting with classmates. He explains his reasoning:

The disclosure meeting was based on the belief that we could nurture the middle schoolers’ innate compassion if we could help them to connect with Mathew’s emotional pain. As a psychologist, I have long been intrigued by a phenomenon that psychotherapists experience all the time but rarely talk about: Therapists don’t necessarily care about new patients who first walk into their office. Yet in nearly every situation, after the patient begins to talk about his or her deep suffering, something magical happens. The therapist quickly comes to care, and often times care a great deal, for this person. […]

But adolescents are famous for their self-centeredness. Were we hoping for too much from his classmates? Martha Snell, a professor of education at the University of Virginia, suggests that due to their stage of development, middle schoolers can barely help themselves from making fun of anyone who is different. She believes that those with disabilities are especially vulnerable.

However, my own experience with adolescents (and younger children as well) has shown that they tend to demonstrate great compassion to a child who is blind, in a wheelchair or has cancer. Their reactions are most likely to be insensitive and even brutal when the disability (such as depression or anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar, Tourette’s or Asperger’s) is hidden and misunderstood.

In bringing the hidden aspect of Asperger’s into the light and explaining how Matthew’s communication patterns worked differently, this principal hoped to teach his students an important lesson. The details of this “disclosure meeting” are beautifully written, carefully conceived and powerful, and I urge you to read them here.

The takeaways are just as critical. The principal describes important changes which continued to persist a whole after the meeting. The students were able to appreciate Matthew as a peer. They were instructed how to intervene in a sensitive manner when he inadvertently disrupted discussions in class, picked his nose or took up too much air time in a conversation. But now, according to Rood, “the students’ intention was to help rather than harass him. This enabled Mathew to stay open and consider whether he wanted to change his behavior.”

Just as importantly, the other classmates’ behaviour changed as well. Matthew no longer ate alone in the cafeteria. The students took satisfaction in helping him find his way, rather than outing him for being different. Rood writes, “They had strengthened their connection to one another by establishing a new social norm: Acts of compassion were viewed as a sign of strength and character.”

Rood urges teachers not to attempt disclosure meetings such as this one on their own. They should be done only with the informed consent of the student and the his/her parents, as well as the active intervention of a school psychologist, guidance counsellor or social worker. Without proper handling, it is conceivable that a disclosure meeting could result in further isolation of the student in question. For more information, I would suggest the excellent accompanying toolkit for planning disclosure meetings.

Want to know more about disclosure for young people with disabilities and those who work with them? You can also download this comprehensive expanded resource The 411 on Disability Disclosure: A Workbook for Youth with Disabilities.